Sounds and Seasons

Bad Diaspora Poems, my poetry collection, came out last summer. I don’t do anniversaries, but I’ve been thinking about the life of a book, the movements and detours it inspires. I’ve been surprised (and at times unsettled) by the collection’s reception. (Shoutout to the judges of the Somerset Maugham Award for a recent unexpected honour). In publishing a book of poems, I knew I was finally rid of them, or rather, they were rid of me. Irresolution might be a natural place for me to write from, a crutch in many ways, but I’ve been tickled by how writing through ambivalence inevitably helps clarify so much in my personal life. In that sense, I find writing productive, or even worse, useful. Yeats defined poetry as the quarrel we have with ourselves, and I reap so much meaning from this struggle, the singing amid uncertainty that he exalted. Like music, this has an intrinsic rhythm, a teetering stutter, the lag and the delay.

In the process of thinking and dreaming up a collection, these songs nudged me, staining my consciousness. Here’s a playlist I compiled last year to listen and feel through. Book anniversaries may feel gauche, but a song, remembered and recalled, has a way of exhausting the inexpressible. When it comes to poetry and thinking through poetry, there’s so much that still feels profoundly, ecstatically inexpressible. It feels good to hold on to some things, to exist in hushed tones, to still have some secrets.

Some songs that informed the sway and sensibility of Bad Diaspora Poems.

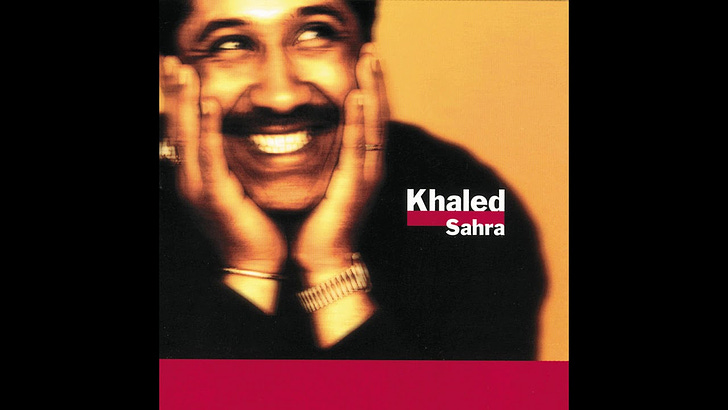

Aïcha, Cheb Khaled

I listened to a lot of Raï while editing. For me, this genre exists in the same soundscape as the qaraami songs of the Somali tradition. Both genres explore the latitudes of interminable, popularised longing. Qaraami is a coastal echo, grappling with ruin in both form and feeling. Raï is a smoke-drenched Parisian cafe, a dive bar in Marseille, a woman choked by debt and disillusionment standing on a stage and eating the audience alive. Raï is the ecstasy of the port, the feeling of standing on the edge and knowing that, across the water, in another language, someone else is planning to blow up their life in exactly the same way. Someone else wants to escape. Oran is irrecoverable. It stinks like a sailor. I love this song because it stays on me.

Tonton du Bled, 113

The summer trip to the motherland is an early reckoning with form. The child, growingly familiar with the contours of their life in diaspora, is flung into relation with what could have been. They meet a gaggle of cousins, their fuzzy doubles, their mirrored image. Comparison and pattern recognition become the order of the day, a collective bonding exercise taking place over plastic tabletops and ice-cold bottles of Hamoud Boualem. “Tonton du Bled” details the disorientation of summer returns. The journey begins by car, cramped shoulder to shoulder, siblings fogging up the windows with their restlessness. Necessities vie for space with luxuries in bulging suitcases. The troublemakers adopt a veneer of respectability, practicing the greetings they will offer to a parade of near and distant family members. They prepare for the inevitable faux pax. A few weeks and it’ll be back to the cocoon of the ghetto, as Rim’K raps wryly. But for now, he swaps a battered leather jacket for a dusty thobe. “Tonton Du Bled” is a classic, a staple of the janky Euro music channels I flicked through on satellite television as a child, my grandmother offering commentary from the sofa. (These channels provided insight into the former Eastern bloc’s musical tastes and the surprising crossover appeal of all my favorite British girl bands). The trio of Rim’K, AP, and Mokobé hop on a ferry, leaving their PlayStations behind and making their way to the village, armed only with cheeky irreverence. The result is an anthem for all the uncles from all the bleds everywhere. RIP DJ Mehdi.

Ostia (The Death Of Pasolini), Coil

This song invokes the angularity of suffering, the sounds of a body being compressed and contorted. It traces a line from Ostia’s resorts to the White Cliffs of Dover. Pasolini is a spectre, haunting the beach where he was murdered, a coastline now frequented by Romans on a budget. Pasolini the idol and iconoclast, the perennial wounded son, the awkward translator, the embattled celebrity. The Pasolini I am fascinated by is the one who transcended the horizons of his birth, who was always seeking to be untethered, letting this impulse lead him to unlikely conclusions. I think of his 1964 poem L’uomo di Bandung, or Bandung Man. Bloody bougainvilleas and intertwined fates. The coarse and the delicate. He writes from Mombasa, Cape Town, the Red Sea, the Gulf of Marseilles, the periphery of Rome. In the realms of hunger – alongside the trust of the loving – there’s also the hatred of those who will not understand.

I return to these lines often. I was in that space for a long, long time.

John Balance, Coil’s co-founder, was another poet searching for the honey in the hollows. 1986’s Horse Rotorvator is one of my favourite albums. Regent Park is captured on its cover. The park’s bandstand, targeted by an IRA bombing in the summer of 1982, takes central position. Another connected explosion at Hyde Park left a scene of carnage. Seven dead horses lying motionless, surrounded by damaged cars. The photographs are hard to forget. You think of your own family photos taken at Hyde Park, bundled in your mother’s arms, wearing a flower-splattered hat. Later, older, licking ice cream by the water. Surreptitiously feeding the ducks. Spotting strange men behind the bushes. The horses lie on the floor like expensive rugs. In 2024, I see an image of two blood-streaked horses running loose through London’s streets, and I am closer to understanding a song as a kind of premonition.

My Dark Star, Suede

Teenage angst is a warm bath you don’t want to slip out of. After some time, your fingertips wrinkle. Your toes prune up. But you don’t care. You luxuriate in being misunderstood, in the delicious agony of a pain that has visited you at much too young an age with too brief an introduction. I listen to Suede in the same way I did as a teenager, divided by years of knowing but not necessarily doing better. The residual obsessions remain. The savage poetry of the council estate. An imagistic understanding of the world. A memorable b-side. Brett Anderson is a slinky voyeur, curling his lip, jerking his hips, surrounded by velvet curtains and condemned lives. He sings of a woman that has come to England from the sea. In writing, I revisit points of departure and arrival, preoccupied with waiting rooms, with the act of waiting for your life to begin, to finally start making some kind of sense.

Nebki Ala Dnoubi, Kamel Belkhirat

Malhun originated in Morocco, a poetic vernacular set to song. Malhun is the throat’s manifestation of the kind of need that colours everything in its wake. It’s a story that begins somewhere and is forced to end elsewhere. My sins are like gravel. Countless, the poet admits. The musician follows. They commiserate over regrets, their negligible virtues.

كثرات سِيّْتي ونْقلَّت حسناتي / وسْجننِّي فَسلاسل الغْدر

The words are borrowed from Muhammad Bin Suleiman, a poet and sheikh from Fes. Malhun can be unforgivingly exposed. Like faith, it wobbles on its legs. Kamel Belkhirat’s voice is a controlled tremor. I listen to this song, pressing against the hollow of its neck. I practice indecision, get so good at it that I frighten myself. I write the book I’m capable of writing to avoid all the books I can’t stop thinking about but won’t allow myself to write. I curse my culpability. I curse my sins. The word tawbah is derived from the root taba, meaning return, recurrence, a turning back. I am trying to write in the spirit of repentance.

Malaika, Miriam Makeba

I’m writing this post from Johannesburg, where I listened to a musician perform a beautiful cover of this Swahili love song in a busy jazz bar. It reminded me of how much I love Miriam Makeba’s version. What more can be said of a woman who made a practice out of endurance? Eighties New York. The cast members of Sarafina!, Mbongeni Ngema and Hugh Masekela’s Soweto-based musical, are met with a surprise. Makeba has come to visit. Their faces drop, then crumple into a haze of tears. They rush to embrace Makeba, an artist who has spent three decades in exile. The youngsters had never seen Makeba, never had the chance to watch her perform. She was a distant icon, like a star you could barely make out with your eyes. A hug bridged what had been so violently uprooted for so long. After his release from prison in 1990, Nelson Mandela convinced Makeba to finally return to her country. In the spring of 1992, she performed in Johannesburg, her first time doing so since 1960, when her passport was cancelled and her life disrupted. Makeba died near Naples, another city of scatterings and reconciliations I wanted to confront in Bad Diaspora Poems.

The half-life of this song persists.