There’s been a resurgent interest in the histories and legacies of militant and third cinema, as well as the infrastructures which sustained the filmmakers at the forefront of these movements. This interest manifests in the ecosystem of restorations, film festivals, retrospectives, and anniversary screenings. Of course, there’s also the circulation of moody, decontextualised screencaps on social media. (All hail the microblogging site as a portal of discovery).

At its best, militant cinema propagandises unashamedly, in formally ambitious ways, against the vagaries of capital and militarism. Naturally, such films become lodestars for a generation reckoning with contemporary political and social upheavals. The 20th century looms over the shoulder, resonant in its promises and betrayals. Militant cinema is a monument to creative self-determination. The canon is crowded with filmmakers who have faced hardship, funding woes, relentless censorship, intimidation, and political repression. Their legacy is a testament to resolve and resourcefulness.

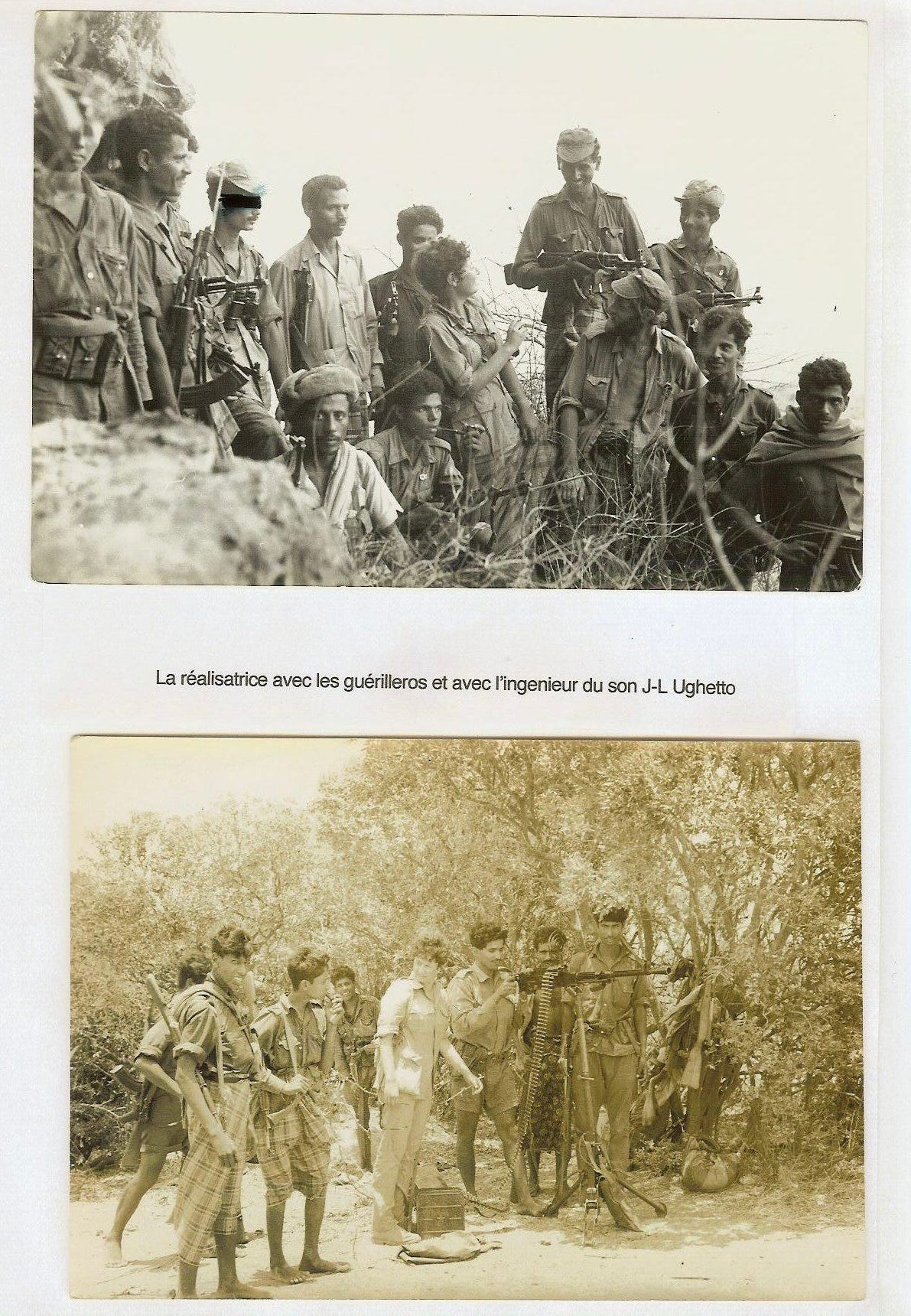

Heiny Srour is one of these pioneers. You might have heard of 1974’s The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived, her directorial debut chronicling the guerrilla movement which erupted in Dhofar in the 1960’s. The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived remains the only documentary attesting to that rebellion, flaring up against the reign of “oil and opportunism” in the Arabian Gulf. The film is a heady conflagration of image and sound, a landmark testimony to the hopes and dreams of the rebels it follows. (It was also banned in Srour’s home country of Lebanon for forty-five years. Too incendiary to be shown in various Arab countries, the notable exception being its distribution by the Algerian Cinémathèque). Srour’s other films, from 1984’s Leila and the Wolves to 1995’s Rising Above: Women of Vietnam, confront muzzled archives, liberating women from their roles as symbols for nations and revolutions.

I spent some time in Paris with Srour, reflecting on her legacy for Bidoun. Srour is a gutsy subject. She’s been through a lot, and is still, aged 80, raring to throw herself into the fray. Admittedly, I was a bit emotionally frazzled when we met, having recently spoken to some of Srour’s contemporaries, as well as other artists who had battled similar struggles and constraints. I was also dipping in and out of a copy of Muthaffar al-Nawab’s anthologised poetry, plucked from the shelves of Librairie de l'Orient, one of my favourite bookstores in the 5th arrondissement. “I have accepted all things except humiliation”, the late Iraqi poet had once written, hounded out of one Arab capital after another, even as he continued to publicly oppose despots and censors. Endurance unsettles me. It inspires both awe and dread. How far can you be pushed? How far are you willing to go? What are you willing to lose in the pursuit of creative and political freedom?

One thing’s for sure, you can’t make these kinds of gambles alone. Srour’s network of accomplices, advisors, collaborators, and influences provided a Tricontinental web of support. Freshly released from Bourguiba’s jails, Tahar Cheriaa, the influential titan of Pan-African cinema, risked his job and safety to champion The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived. Fellow Lebanese director Borhane Alaouié suggested shooting locations for Leila and the Wolves. Omar Amiralay and Mohammad Malas, two giants of twentieth-century Syrian cinema, offered assistance and advice. In this sense, Srour’s oeuvre bears the evidence of riotous love.

The rebels depicted in The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived were isolated. Lacking regional support, they were weakened by the Sultan’s army and its firepower, British bombs, and the Shah of Iran’s brigades. Their final defeat came in 1976, though it took a few years for the resistance to peter out. One quintessentially Srourian anecdote that struck me during our time together occurs decades later, in the new millennium. An ex-guerilla connected Srour with his son who had arrived in Paris as a student. Srour showed the young man around as he described his father’s severe depression after the revolution’s demise. In a cruel twist of irony, he had only been able to find work in the Sultan’s army. Yet, he still sent his son as a messenger; he wanted Srour to know that he had been one of the last rebels to surrender.