New Year. New Friday poem.

Jeremy Reed is one of my favorite living British poets. For decades, he’s been a prolific, counter-cultural presence, pumping out book after book. According to Reed, British poetry is “socially constrained by its politeness”, an impediment that Reed hasn’t allowed to restrict his imagination or his ability to furiously create out of a corner. I love how he’s written two books on Marc Almond, because obviously one isn’t enough.

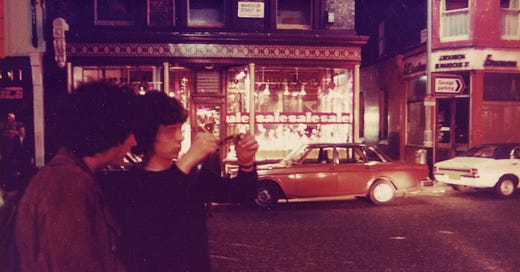

Reed is attentive to time and place, to the particularities of those characters who haunt the ragged fringes of urban life. London is his playground, from the Eighties stink of Thatcherite finance-fuelled opulence to the scruffy glamour of the city’s bohemian underbelly, Reed vividly captures and bottles the energy of a moment, an encounter, a gesture, an absence. He does so with a petulant love, writing out each book by hand and careening up and down personal and historical timelines. His poems are pungent with the mundane and happenstance, with evocative recollections of friends, collaborators, mentors, muses, inspirations, lovers, and assorted vagrants. They echo the familiar feeling of a midnight comedown shared with a friend at Bar Italia and the accompanying wagging of coffee-burnt tongues. They are humid blasts of affection. This is a vision of London that Reed refuses to give up on. It’s one I’m trying to remain open to, despite the odds.

I will leave you with this elegy by Reed, dedicated to the expatriate American poet and publisher Asa Benveniste, a co-founder of the influential Trigram Press.

Asa Benveniste

The thin one. Belsen, Dachau-thin,

black T-shirt under a silver

cashmere V neck:

your voice smoked from Camel filters,

a quiet New York inflected baritone

resonant as Leonard Cohen’s

phrasing from a thoracic well,

each word selected for its body weight

in gravity.

You wore a Saturn-shaped blue opal ring

like a poem, sparkly planet

drawing the eye to its slow-burn pulsar,

my first impression circa 1970,

a foghorn blowing growling sax offshore,

you flying in and out that day –

here for my burn-up poetry

you claimed had a leopard’s heartbeat

inside its derivative imagery,

a flavour, just like Rimbaud, so you said,

in hallucinated intensity.

You wanted twenty-five for a first book

from Trigram: you the handsetter

raising ink off the page like a cobra,

its bite into paper so clean,

you felt the raise like black nail gloss

as the printer’s signature.

You were London’s small press cult publisher,

bringing me books – Raworth, Jim Dine,

injecting trust in me to have my hand

walk like a shoeless nomad on the line

I still keep now. You ate yoghurt

instead of meals, and got race circuit highs

from volatile Turkish coffee,

published outsiders with impunity,

worked at your own poems, a Jewish rite

of fetching kabala to verbal chemistry,

and had the tree of life tattooed

in black and scarlet on your nape.

You got me to London. I owe you all

the shape-shifting miles I’ve tracked on the page.

You died an amputee, your left leg stumped

like Rimbaud’s, eaten by diabetes

and gangrene.

Your chess partner was a whiskey bottle

progressively losing out its level

to your tried hangover immunity.

Your last poems were like morning glories,

lyrical, blue, scented like the Tangier

you’d lived in 1953.

I see you still, the foggy day we met,

me naive, disingenuous, and you

already my instructor, thin blue jaw,

saying half in humour, but more in truth,

poets only live by breaking the law.